When I was growing up, I had an Aunty Lily who featured greatly in my life – she was actually my great aunt, Lilian Gertrude Pursell, the elder sister of my paternal grandmother, Nanna Cockrill. But later, when I began delving into my family history, I discovered I had another great aunt Lilian, Lilian Dorothy Cockrill, the younger sister of my grandfather, Ernie, and therefore Nanna Cockrill’s sister-in-law. It’s the latter, the elusive Lilian, I’d like to talk about here.

The Letter

(If you need to ‘follow along with the song sheet’, a quick reminder that the family tree is here).

On first learning about Lilian Cockrill around 40 years ago, she intrigued me. What intrigued me most, and perhaps disappointed me as I grew older, is that I never met her. But could have. She died in 1972 when I was 12 years old. Not having the opportunity to meet her had a lot to do with the Great Cockrill Family Rift which needs a blog post (or two) to explain in detail but I will give you an inkling as I begin to unravel Lilian’s story here.

The only two pieces of information I had about Lilian was a tantalizing scandalous family story (I’ll get to that later) while the other was more tangible: a letter she had written to my father in 1945, just after the end of World War Two.

I am not sure why this correspondence was kept but it has been invaluable. I’d love to share it with you here, but the letter is currently back in England. However, I do remember certain revelatory details within the contents. There were basic facts like Lilian’s address in Hampstead in north London, and her married name Bruce. Mrs L.D. Bruce was written on the back of the envelope and, thanks to my old-fashioned primary school that taught me traditional letter writing etiquette, I knew that the use of her own initials and not that of her husband’s indicated that she was either divorced or widowed. There were also more subtle nuances that gave an insight into her education and personality. It was a well-written letter, in format and style. It was also warm and chatty. She talked as if she knew her nephew (my dad) quite well and looked forward to catching up after the war. It was also a wonderful piece of social history as she admitted (if I remember rightly) to ‘getting squiffy’ on the day war ended – 8 May 1945 – VE (Victory in Europe) day.

Sadly, I don’t think my father and she ever did catch up after the war. It seems Lilian’s attempt at making peace with my father at a time of world peace never came to pass. Nanna Cockrill apparently purposely distanced herself from the majority of my grandfather’s family, caused by a series of situations which would fit admirably into a BBC East Enders storyline. This is how I understand it. Firstly, my grandfather Ernie left home as soon as he could because his mother (Sarah Ann Hollingbery) replaced his father (Albert Edward Cockrill) with someone else; secondly, later my grandfather fell out with his younger brother (Laurence William Cockrill) because Laurie took his ‘patch’ whilst they were in business together as coal merchants. And thirdly (drum roll) apparently Lilian was ‘a madame in Soho’. I longed to find out whether this was fact or just family hearsay based on disapproval and misunderstanding of her lifestyle.

Seemingly, the only time Lilian came into contact with our family again was in 1967. This was on the death of her mother (Sarah Cockrill née Hollingbery). She called upon Nanna Cockrill in Hackney to inform her of the fact. Nanna Cockrill and her mother-in-law (my great grandmother) lived less than a mile away from each other but had remained estranged for over 30 years.

And so, over the years I have taken up the challenge of looking for Lilian. Or was she known as Lily or Lil? Who was she? Perhaps we shall never really know but with the help of Ancestry, FindMyPast and British Newspapers Archive and many other online resources, I am beginning to build up an, albeit hazy, picture.

Growing up in Hackney

Lilian was born into a new Edwardian era on 14 July 1901 to my great grandparents, Sarah Ann née Hollingbery and Albert Edward Cockrill. Following the death of Queen Victoria six months previously after a 63-year reign, England and the Empire were becoming accustomed to her son assuming the role of King Edward VII. Lilian was born the first girl into a family of three boys all close in age. Their new sister was no doubt a novelty to six-year-old Albert, to Ernest (my grandfather) who had just turned five a week before she was born, and to Frederick, almost four. She was to be the only girl in the family for there were three more brothers to come. At the time of her birth, the Cockrill family were living at 37 Swinnerton Road (London E9 5RG), a short walk away from Homerton High Street where Lilian was christened at the Parish Church of St Barnabas when she was four weeks old.

A 1905 map of the area shows us that Swinnerton Road lay between the grim Hackney Workhouse and Mabley Green, a piece of common land that is separated from the Hackney Marshes beyond by the River Lea, which wends its way from Bedfordshire, down to the Thames at Bow Creek. The Hackney Workhouse is no more but Mabley Green has been a recreational area since the 1920s, now with an Astroturf football pitch and more recently a famous giant boulder for rock-climbing. The old map also shows us that the Great Eastern Railway (GER) North London Line ran close by, with a station at Homerton and also at Victoria Park. A stone’s throw from their house was the GER Hackney Wick goods yard. It was here one assumes where Lilian’s father, my great grandfather Albert worked, as in the 1901 census he is listed as a Railway goods porter, ie employed to load, unload and distribute goods on the railways. The GER had operated in this area from 1872, developing considerably around the 1890s to service the expanding suburbs of northeast London and to connect with the main line to Cambridge. It was absorbed into the London North Eastern Railway (LNER) when the country’s railways were grouped into four companies following the Railways Act of 1921.

There were several other men in Swinnerton Road, who were also railway employees. The Cockrill family shared the house with the Parnells, similar in age. One assumes that each family had a floor of the house. John Parnell was a Railway Goods Checker – no doubt intrinsically linked with Albert’s job but did they also ‘hang out together’ at home? John’s eldest son George was the same age as little Frederick Cockrill, while his daughter Ada was around a year older than Lilian. One can imagine that perhaps the families visited Victoria Park together on Sundays, for the Molesworth gate was just 10 minutes’ walk away. Since 1865 the park had been a welcome haven for East Enders with its 213-acre boot-shaped expanse of grass, containing both cricket and football grounds, and three small lakes for boating and bathing.

Both the world at large and Lilian’s world changed dramatically again by the 1911 census, held on the night of 2 April. King Edward VII had died the previous year and his son was shortly to be crowned King George V. By now, Lilian had lost her brother Frederick, who died aged only five in 1903. She had also lost her father who at some point left the family home (and so far, frustratingly without trace) in around 1905. The circumstances are mirky but what is clear, as attested by the census return, is that it was Albert’s older brother James Cockrill who took his place. Lilian now had three more brothers, Reginald, Percy and Lawrence, the last two being fathered by James, according to their baptismal records. One can only imagine the nature of the family dynamics at this point. However, within a few short years, the world and individual families were transformed again by the Great War, later known as the First World War (WW1). Lilian’s two older brothers Albert and Ernest (Ernie) both enlisted but only one returned. Albert Henry Cockrill was killed in action at the Battle of Loos in France on 13 October 1915. Ernie served overseas in Egypt and Salonika but was discharged from duties through ill health in 1916. Returning to England he chose to live with his grandmother (my great great grandmother) Emily Hollingbery because of tensions at home due to his mother’s relationship with his uncle. In 1920 Ernie married Florence Daisy May Pursell, our Nanna Cockrill.

But let’s head back to Lilian’s story. By 1921 she was 19, almost 20, living with her mother and stepfather/uncle, and three younger brothers, at 22 Berkshire Road, Hackney Wick which was the Cockrill family home from the WW1 period for many years to come. Lilian was a shorthand typist for Achille Serre Dryers Ltd which was based in a large factory on White Post Lane in Hackney Wick, just a 5-minute walk away. By the mid-1920s, the company employed 1500 people and serviced well over 100 shops in the southern half of Britain. It had been started by Parisian ribbon dyer, Achille Serre in the 1870s who first introduced ‘dry cleaning’ to Britain. The company lasted 100 years and was later bought by Sketchleys. The business’s success was due to having the latest machinery as well as high standards of service. Advertisements for the company in newspapers and journals such as the literary and society periodical, The Tatler indicate their clientele at this time: those that enjoyed the high life and needed their gowns, furs, feathers cleaned on a regular basis. Lilian was perhaps beginning to encounter a different world to her working-class East End past.

New Life in North London

When Lilian was in her 20s, she moved out and headed for north London, where large 19th century houses were being divided into short and long term lets for those working in central London, easily accessible by public transport. Throughout the late 1920s and most of the 1930s she lived at two different houses in a long street called Adelaide Road (now the B509) in NW1, in walking distance to Primrose Hill and Regents Park. I love the connection with Adelaide in South Australia, my hometown for the last 20 years! In fact, both the road and the city were named after the same person, Queen Adelaide, formerly Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, and later Queen Consort of United Kingdom and Hannover, as wife of King William IV from 1830-1837. Adelaide the city was founded in 1836, while the road on the other side of the world began to be actively developed at about the same time.

Llewellyn Stephen Bruce

However, there was a brief period that Lilian was married, (roughly four years) when she lived with her husband Llewellyn Stephen Bruce in the leafy, north London suburb of Haringey at 26 Langdon Park Road (N6 5QG). According to their marriage certificate, he was a 27-year-old ship’s officer, the son of a retired Metropolitan fire brigade officer. She was two years older and interestingly, no job was noted next to her name on the certificate. They married on 10 January 1932 at the Parish church of St Clement’s Barnsbury on Westbourne Road (Islington). This Early English style church of 1865 was the work of renowned architect Sir George Gilbert Scott who, incidentally, was designing the famed Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens around the same time. Today, the church is a Grade II listed building which has been turned into very expensive flats known as St Clement’s Court (60 Arundel Square, London N7 8BT, accessible from Davey Close).

None of the Cockrill or Bruce families appear to be witnesses at their wedding. At the time, Lilian gave 98 Bride Street as her address, a 2-minute walk to the church and the home of William Hosking, a retired policeman and his family, where one assumes she lodged. William’s son in law, Ernest William Rodley, was one of their marriage witnesses.

There’s something about a sailor

It was short-lived marriage, and more research has uncovered a colourful life that may have been the initial attraction but also perhaps the downfall of the relationship (although this is pure speculation).

Llewellyn was born in Twickenham to Emily and James Carlton Walters Bruce. His father James had been married twice before. Llewellyn had a half-brother James Walters Nicholson Bruce almost 10 years older, whose mother Louisa was his father’s second wife. James Bruce Senior was born in Swansea, Glamorganshire. His father, William (Llewellyn’s grandfather), hailed from Cornwall and was a mariner. At some point James moved to London and joined the Metropolitan Fire Brigade. However, by the time he was 50 he had been pensioned off and during Llewellyn’s childhood, was employed as a fireman at the Carlton Hotel in Central London. In its early days, when run by the famous Swiss hotelier, César Ritz (‘King of Hoteliers, and Hotelier to Kings’ who gave us the term ‘ritzy’), the Carlton was one of London’s most fashionable hotels operating from 1899 for almost 40 years. It was situated on the corner of Haymarket and Pall Mall, adjacent to Her Majesty’s Theatre. Demolished during the 1950s, today the site is occupied by the 17-storey block of the New Zealand High Commission.

Llewellyn’s father James was proud of his Welsh origins. After all, he had given his son a patriotic first name: Llewellyn, Welsh for ‘like a lion’, or ‘leader’. In the 1911 census return, James stated he is ‘Welsh’ in the Nationality box while in the 1921 return he is even more daring. In the Birthplace box, he wrote ‘Salubrious place’ underneath ‘Swansea’ indicating its health-giving properties! The family at that time were now living in Wales, where they had shifted in around 1915, very likely indeed for James’ health. Working as a fireman in inner city London would have taken its toll. Home for Llewellyn was now at Llansteffan, a small village on the south coast of Carmarthenshire, on the estuary of the River Tywi. A Welsh-speaking part of Carmarthenshire, the Llansteffan peninsula was, and is, a beautiful stretch of coast, with sandy beaches, surrounded by farmland, an ancient castle on the hill while at the time, it was also possible to cross the estuary via ferry. The area also has strong family links with Dylan Thomas. This famous Welsh poet spent his childhood summers during the 1920s holidaying in the area and we know he often stayed with his aunt at Rose Cottage on Old School Road. This was on the same street where Llewellyn’s parents lived (2, Bryn House, Llansteffan, Carmarthen SA33 5HA). Watch this short video of the Llansteffan long walk from Carmarthenshire County Council to get an idea of the beauty and history of this area. I certainly want to visit!

Both Llewellyn and his older brother James went to sea like their grandfather. James joined the Royal Navy when he was 16 years old. He married local Llansteffan girl Rosie John in 1916 when he was an Officer Steward, First Class serving on the HMS Hibernia, part of the Grand Fleet. During WW1, this ship frequently went to sea to search for German vessels and in 1915 the Hibernia played an important part in the Gallipoli Campaign. James and Rosie were to have three daughters who later helped their mother run a public house in Plymouth whilst their father was at sea.

Llewellyn also joined up at 16 but to the Merchant Navy. According to the 1921 census return, he was out of work at 17 although he had been employed by the Cardiff ship owners, D.R. Llewellyn Merrett & Price Ltd. In 1927 he appeared to be travelling regularly across the Atlantic from the Victoria Docks in the Port of London to New York on the RMS Carmania. According to crew lists, by the end of the year, he had been promoted from Able Seaman to Quartermaster and we learn that he was 5’ 7” tall. Carmania was a Cunard Line transatlantic steam turbine ocean liner and with her sister ship RMS Caronia, had once been the largest ships in the Cunard fleet. The prefix RMS meant she was a Royal Mail Ship, carrying mail under contract to the British Royal Mail. Launched in 1905, the following year the ship took famous science fiction writer, HG Wells on his first voyage to North America. Back then, the Carmania had been a luxurious ocean liner carrying over 2500 passengers in four classes. During WW1 she had been converted to an AMC (Armed Merchant Cruiser). However, by the time Llewellyn was a crew member, she had been refitted as a cabin class ship and kept busy until the shipping slump at the end of the decade due to the Great Depression and scrapped in 1932. One of her bells is on display aboard the permanently moored HQS Wellington at Temple Pier, Victoria Embankment, London, while another is at the Clydebank Museum in Glasgow. Check out this short presentation from Ballins Dampfer Welt which gives a great idea of life on board the RMS Carmania during the 1920s.

In 1929, Llewellyn spent six days in the Dreadnought Seaman’s Hospital at Greenwich having his T&As (tonsils and adenoids) removed. At that time, he was a Quartermaster on the P&O passenger ship SS Macedonia, which had been built by Harland & Wolff in Belfast in 1903, the same shipyard that had produced the infamous Titanic almost a decade later.

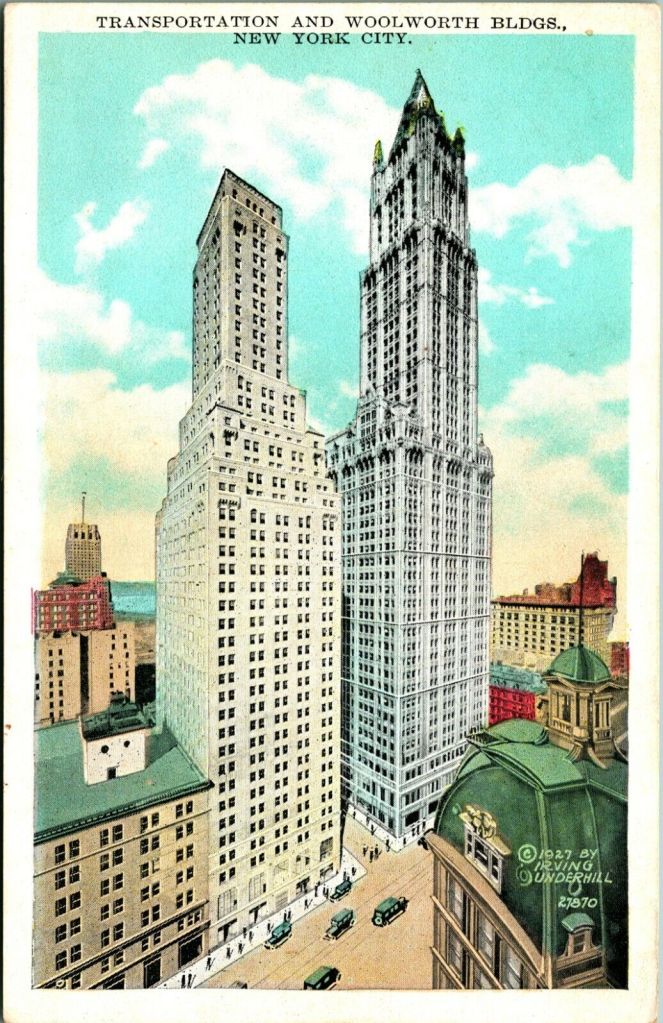

However, according to the hospital register Llewellyn’s home was cited as 31 Harewood Ave, W1 (London NW1 6LE) close to Marylebone station. It is only supposition, but did he perhaps first meet Lilian whilst on shore leave at a London club, ‘up west’? Did he regale her with his seafaring tales including his visits to New York? It would have been a fascinating time to have experienced the ‘Big Apple’, where the skyline was literally growing before one’s eyes and world changing events were taking place. We know he did at least four trips to New York in 1927 during the peak of the skyscraper building spree (1925-31). As he sailed into port, he would have spotted the then tallest building in the world, the Woolworth Building at 233 Broadway in Manhattan, which reached a height of 792 feet (241m). The Empire State Building on Fifth Avenue at 34th Street (1,250 feet or 381m with double the number of storeys) was yet to be built, being completed in 1931.

In addition, 1927 was the year pioneering American aviator Charles Lindbergh made the first transatlantic, solo, non-stop flight, successfully crossing the Atlantic Ocean and landing in Paris less than 34 hours later. He took off from Roosevelt Field, an aerodrome on New York’s Long Island, in his Spirit of St Louis monoplane.

And it was also the year that heralded The Jazz Singer, the world’s first ‘talkie’ – the first feature length motion picture with synchronised dialogue. Was Llewellyn in town on 6 October to experience the opening night crowds spilling out on to the sidewalk at New York’s Warner’s Theatre?

Lilian and Llewellyn went their separate ways in around 1936, Lilian back to her old life in north London while as far as we know, Llewellyn continued his seafaring ways. Maybe that was the problem.

In 1939 Llewellyn was sharing accommodation at 55 Eastlake House, a block of flats in St Marylebone and was a Ships Quartermaster on the SS Rajputana, a P&O British passenger and cargo carrying ocean liner. In the past, her passengers had included Lawrence of Arabia travelling from Karachi to Plymouth in 1929 and Mahatma Gandhi from Bombay to London in 1931. Llewellyn was probably on one of the ship’s last voyages before she was requisitioned by the Admiralty to be used as an armed merchant cruiser for the coming war. Fortunately, Llewellyn was not on board when the Rajputana was torpedoed and sunk off Iceland by a German U boat in 1941.

Merchant seamen crewed the ships of the British Merchant Navy which kept the UK supplied with raw materials, arms, ammunition, fuel, food, and all of the necessities required by a nation at war throughout WW2. As a result, they sustained a considerably greater casualty rate than almost every other branch of the armed services and suffered great hardship. Research has shown that Llewellyn had two lucky escapes. He was one of six quartermasters on board the SS Malda which left the port of Newcastle at North Shields on 21 May arriving in New York via Halifax, Nova Scotia on 4 July (American Independence Day!) in 1941. However, less than a year later, on 6 April 1942, she was attacked by Japanese aircraft and then sunk by naval gunfire from IJN (Imperial Japanese Navy) heavy cruisers. At the end of 1941, Llewellyn arrived in Glasgow on the P&O Viceroy of India. It was Britain’s first large turbo-electric passenger ship, and a British Royal Mail ship on the Tilbury Bombay route but the previous year had been requisitioned as a troop ship. In November 1942, she was sunk by a German U-boat in the Mediterranean.

But Llewellyn survived the war. He remarried Beatrice Lowe and had two children in the 1940s and they were living in Romford in the 1960s. Llewellyn lived out his final years in the small seaside town of Holland-on-Sea, between Clacton and Frinton-on-Sea in Essex. He died aged 79 in 1983.

Watch out for Part 2, when I continue my search for my great aunt Lilian.