Time to explore a story from my mother’s side of the family which seems appropriate seeing that mum recently celebrated her 99th birthday, in Market Harborough, her home now for almost 35 years.

Market Harborough: the coolest place to live

In 1989, my parents moved from Purley, south of London to Market Harborough, this small Leicestershire market town, close to the Northamptonshire border. After living all their married life in the London area, they chose Market Harborough as their new home because of its relative proximity to my brother and sister and their families. It had been a town we had often driven through when I was at Leicester University, and it had a nice feel to it. It still does although it has expanded considerably since then, becoming a popular town for London commuters. It’s now less than an hour by nonstop train down to St Pancras. And apparently, as of March 2023, it is considered one of the coolest places to live in the UK.

Market Harborough has a few claims to fame: the Liberty bodice, which helped change the way children dressed in the early part of the twentieth century, was invented here at the Symington’s corset factory; Britain’s iconic HP Sauce was once made here (the factory closed down in the mid-1990s but I still remember the all-pervasive pungent, spicy smell wafting over the town when Mum first moved there – Sainsbury’s is now on its original site); and erstwhile woodturner, Thomas Cook (1808-1892) was living and working in Market Harborough in 1841 when he organised a train excursion from Leicester to Loughborough for nearly 500 people for a shilling each. This was to be the very first package tour and led to the establishment of his world-famous (but sadly now no more), Thomas Cook & Son travel agency.

As an aside, I’ve discovered there is even a direct connection with my current hometown, Adelaide in South Australia. An iconic feature of Market Harborough is the 17th century Old Grammar School in the town centre, raised on stilts so that the local farmers’ wives could use the space beneath as their weekly butter market. The school’s most famous former student was William Henry Bragg (1862-1942), who later shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1915 with his son Lawrence Bragg for their work on x-ray crystallography. William Bragg had begun his research into X-rays and wireless telegraphy at Adelaide University where he was Professor of Mathematics and Experimental Physics for over two decades from 1885-1908 before returning to the UK. His wife (and Lawrence’s mother) was Gwendoline Todd, the daughter of Sir Charles and Alice Todd (who famously lent her name to Alice Springs, my previous hometown for 12 years). But that’s another story!

Let’s return to this story. So it appeared there was no direct connection with our family to Market Harborough. Or so we thought. After delving deeper into my mother’s family history recently, I was amazed to discover that in fact we had relatives who lived, worked, and died there from the early 1900s.

And a reminder again, the family tree can be found here to perhaps make it easier to follow along. If you have trouble accessing it, contact me and I’ll share the link with you.

The Brunnings connection

Let’s set the scene. First, we need to head to East Anglia and count some sheep. Or rather shepherds. There were rather a lot of them in the family.

My maternal grandmother, Nanna Betts was Annie Brunning before she was married and hailed from Suffolk. Her father, mum’s grandfather was Charles Brunning. Although he died in 1930 when Mum was just six years old, she does recall him – a slightly grumpy old man, with a large beard, living at Little Cressingham, a tiny village 8 miles (13 km) south of Swaffham in the Breckland District of Norfolk. The oft-repeated salient detail was that our great grandfather was a shepherd. In fact, Charles was from a family of shepherds, going back at least two generations, possibly more. Born in 1845 in the Suffolk village of Icklingham, 7 miles (about 11 km) northwest of Bury St Edmunds and 9 miles (about 14 km) southwest of Thetford, Charles was one of 14 children – six boys and eight girls. Four of Charles’ five brothers were shepherds like himself, and according to census returns had all begun from a young age, about 10 or 12, as shepherd’s ‘pages’ (young male assistants). Their father, my great great grandfather, Michael Brunning, was also a shepherd and was similarly born and bred in Icklingham.

Counting cousins

Not only did I find myself counting shepherds but also cousins. With her father Charles having so many siblings, it meant that Annie, our Nanna Betts, possessed numerous first cousins on the Brunning side. I’ve calculated at least 40 (there may be more but I was unable to trace the family line of a couple of Charles’ sisters).

Discussing shepherding in 19th century East Anglia can wait for another day. Here I want to focus on just one cousin whose story jumped out at me. He needed further investigation because he not only chose to veer from the well-worn path of shepherding, but he also left Suffolk. George Brunning. Just George. No middle name. Fourteen years older than Nanna Betts, he was born in the Cambridgeshire village of Dullingham on 27 February 1881 to Samuel Brunning and Sarah Ann née Frost. His father Samuel was the younger brother – by five years – of my great grandfather Charles Brunning. Unlike his five brothers and his father who were all shepherds, Samuel was an agricultural labourer who later worked specifically with horses. With my own love of horses, this was another aspect that caught my eye. At the time of his son George’s baptism on 16 June 1881, Samuel is described as a horse keeper, and is still so by the time of the 1891 census. In that year we find him lodging with the Fuller family, at Wickhambrook, Suffolk, a village about 10 miles (16km) southwest of Bury St Edmunds. But where was his son George, Nanna Betts cousin? Ten-year-old schoolboy, George was about 15 miles (24 km) away in the village of Rushbrooke, living with his mother, sister and grandfather in North Hill Cottage. His sister Louisa, 12 was also at school and another sister Annie, we discover, was born later that year. The family eked out a livelihood the best they could. George’s 75-year-old paternal grandfather Michael Brunning had moved in with them following the death of his wife Sarah (née Smith) the previous year. Although once a shepherd, he had work as an agricultural labourer, as did most of the men in the area (or as gamekeepers, like immediate neighbours). George and Louisa’s elder sister Ellen was missing from the household. Then aged 15, she had already left home, probably employed in domestic service.

Just George

George followed in his father Samuel’s footsteps. At first anyway. According to the 1901 census returns, they were both grooms. In Little Whelnetham, a tiny village just north of Rushbrooke and about two miles (about 3 km) from Bury St Edmunds, we find Samuel Brunning back at home with wife Sarah. With them was their youngest daughter Annie, just a bump in the last census, but now about to celebrate her tenth birthday. George’s grandfather, Michael Brunning was no longer living with them. He had moved to Bury St Edmunds to reside with Matilda (now Mrs Gill) one of his eight daughters, and her family. He died here in 1905.

It seems that George was sent away to another Suffolk village to learn his trade as a groom but one with close family ties. In 1901, 20-year-old George was some 10 miles (about 16km) away in Hartest. Did his father Samuel beg a favour from his older brother Charles Brunning? Charles was married to Annie Kimmis (Nanna Betts’ mother, my great grandmother), and generations of the Kimmis family had lived in Hartest, halfway between Bury St Edmunds and Sudbury. At the time, Charles’ parents-in-law, George and Louise Kimmis were running the post office on the village green. George was a well-known and respected member of the community, being postmaster, former Parish Clerk, and moreover, a shoemaker, just like his Hartest born and bred father, John Kimmis. Did Samuel ask whether they could find a position for his son within the village or perhaps they suggested the idea to him? Despite being in their sixties, George and Louise appeared to like taking younger members of the family under their wing. At this time, they had their three grandsons living with them at the Post Office: 19-year-old George Redgrave, the son of their daughter Georgiana whose first husband had died tragically within a year of their marriage; and brothers George and Ernest Kimmis, 14 and 12, whose mother Sophia, wife of their son William, had died five years previously. Explaining it another way, these three boys were all Nanna Betts’ cousins on her mother’s side. One likes to think that they welcomed George Brunning to Hartest, sometimes meeting on the green after work to chat about their day.

In the heart of Hartest

Today, Hartest has its own community website and Facebook page. The village is proud to proclaim that it is unique – apparently no other village/town or city in the world shares the same name Hartest! A well-known contemporary resident since the mid-1990s, is Terry Waite, the former Archbishop of Canterbury’s envoy who became a household name after being taken hostage in 1987 by Islamic fundamentalists and enduring five years of captivity in Beirut.

Hartest – A Village History, researched by the Hartest Local History Group and edited by Clive Paine, gives a more detailed account of how the village developed. However, in brief Hartest dates from 1086, features in the Domesday book and its name is Old English for ‘Hart (Stag) Wood’ – a wooded area where deer roam. On the north side of the village green is a large limestone boulder known as the Hartest Stone. There is a family photo of mum sitting on it in the 1930s. The stone’s origins vary, but it is thought to have been dragged there in the early 18th century. One might even speculate that George Brunning may have perched on it at some point, (especially as a local tale says that sitting on it at midnight will lead to either a wife or a fortune). The stone was certainly close to where he was living in 1901. The census return for that year records George as lodging in one of the ‘North End’ houses in Hartest with 38-year-old fellow groom Frederick Topple.

And within seven years, George’s fortune had indeed changed.

A new life in the Midlands

Did George have itchy feet? Maybe it was his house mate who put ideas into his head about travelling further afield? In the early 1890s, Frederick Topple had worked as a groom at Beckenham Place stables, once part of the estate of a Georgian mansion in Kent (but today is an arts, cultural and community centre, a stone’s throw from suburban Sydenham).

Local newspapers as well as The Field, The Country Gentleman’s Newspaper reveal the types of jobs advertised at the time, for those wanting or offering work with horses. Is this where George found the position as a groom in Welford in Northamptonshire, or did he have a contact there? We shall probably never know. Whatever the incentive, this was a big move for a young man in the early years of the 20th century, almost 100 miles away, across two counties, leaving where he and his family had lived for many generations. The village of Welford is halfway between Northampton and Leicester (on the Welford Road, now the A5199) and had been an important stagecoach stop. In the 1911 census return, George was not only a groom living in the High Street of Welford, but his personal life had also dramatically changed. He was now married with a two-year-old daughter. His wife Emily was a local Welford girl, who grew up there with her parents, brother and two sisters. Coincidentally, her sisters were also called Ellen and Annie, just like George’s. Perhaps this had been a talking point when George and she first met? Emily’s father, Jonathan Woodford was a house painter and decorator.

And this is where our past and present family histories collide.

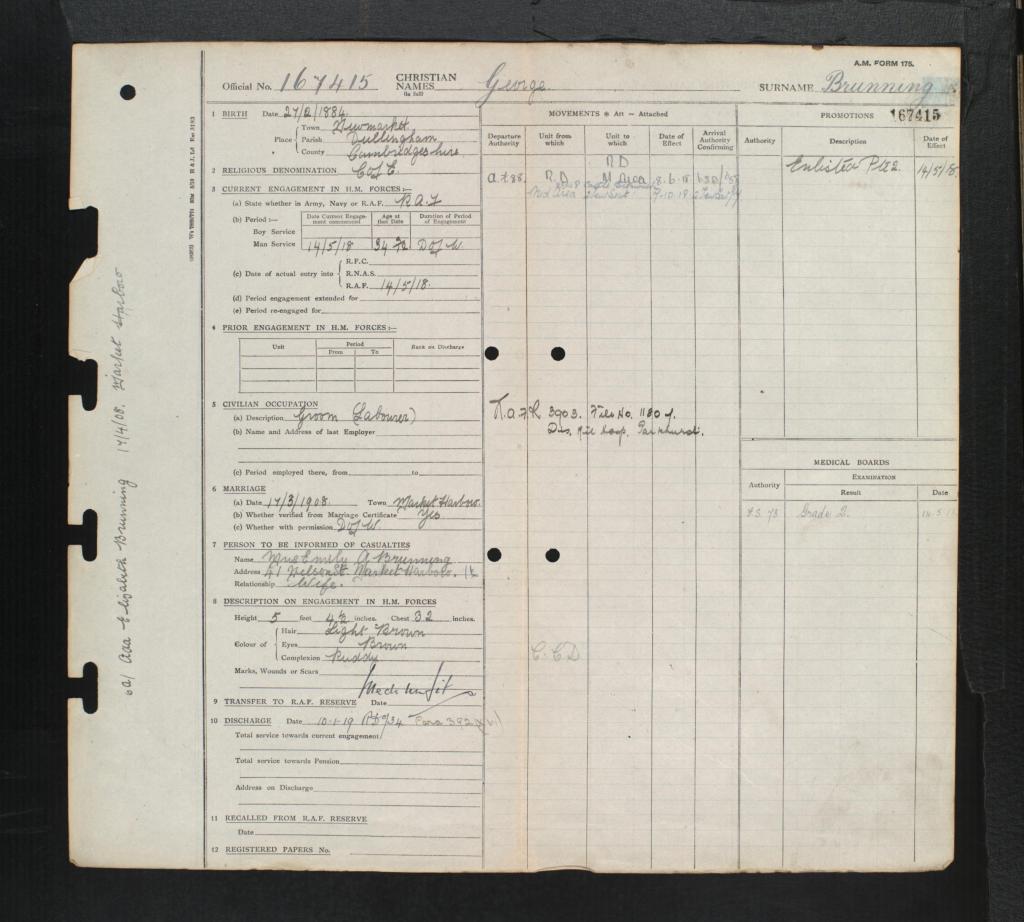

On 17 March 1908, George Brunning married Emily Amelia Woodford in Market Harborough. Evidence for this was in the Civil Registration Marriage index for the first quarter of that year but it was also verified by a wonderful document accessed via FindMyPast: George’s service records when he joined the very newly formed Royal Air Force (RAF) on 14 May 1918.

As well as George’s marriage details and the fact that he is still a groom in 1918, there are a wealth of other useful and fascinating details within the document. We learn that he was 5’4½“ tall, with light brown hair, brown eyes, and a ruddy complexion – a typical country boy. However, this description immediately makes me recall Auntie Billy’s rosy-red cheeks – her mother May Chase née Brunning, Nanna Betts’ elder sister, was also George’s cousin. (We grew up with Mum’s ‘Auntie Billy’ who in fact was really her cousin and christened Alice). It appears that George joined the RAF whilst living in Market Harborough. George and Emily’s address was given as 41 Nelson Street, (LE16 9AX) where we later discover was their home for the rest of their lives. Nelson Street runs parallel with Coventry Road and the house is still there – a typical two up-two down, red brick terrace house. It would take about 10 minutes to walk to the town centre. We also discover that their daughter, Ada Elizabeth Brunning (probably named after Emily’s mother Ada Woodford née Norton) was born on 17 April 1908 in Market Harborough – not long after their wedding. There are some grey areas regarding when and why they lived, married, worked in Welford and Market Harborough at this time but this might relate to the timing of Ada’s birth – or not at all. Another possible reason for shifting to Market Harborough was that Emily’s older brother, John Woodford, a painter and decorator like his father, had moved there in around 1901. The census return for that year shows he lived at 9 School Lane (LE16 9DJ), off Coventry Road with his wife Mary. They lived in Market Harborough for the rest of their lives, and their three children were all born there.

Horses for Courses

In the early years of the 20th century, horses were still crucial to farm work and general transport giving plentiful work for grooms. Grooms managed all aspects of horse care and maintenance, not just grooming but also feeding, exercising, harnessing up, cleaning yards, stables and tack while some knowledge of animal husbandry and medical skills was also necessary. Leicestershire and particularly Market Harborough was the perfect location for an aspiring groom like George. In the heart of rural England, Leicestershire has historically had strong equestrian links and is also considered the birthplace of fox hunting. The fox remains a recognisable logo for the county which boasts five hunting packs, including the world’s oldest, the Quorn Hunt which dates from the 17th century. For George, there would have been plenty of work, more so than in Suffolk, and perhaps better paid.

George moved to Market Harborough at the time when it was the centre of various hunts, the chief of these being the Billesdon Country Hunt. This had been formed in the mid-19th century out of the southern section of the Quorn, which had always been described as the ‘Harborough country’ and considered by many as the cream of the Quorn Hunt. Billesdon particularly prospered under the leadership of Charles Fernie who, from the 1890s, was Master of Fox Hounds for 31 seasons. The hunt became better known to its members and worldwide as Mr Fernie’s, eventually becoming Fernie’s Hunt or just the Fernie Hunt. Harborough overtook Melton as the centre of the fox hunting world and apparently a Monday or a Thursday with the Fernie was a much sought after day in the hunting calendar.

The Fernie hunting area was relatively small – about twenty by fifteen miles (30 x 25 km) in extent, entirely in South Leicestershire but considered ‘the best grass country in England’ with few ploughed up fields, and more or less ‘wireless’, that is without wire fencing to impede the sport. Charles Fernie had made the hunt so popular that the area was being hunted seven days a fortnight during the season compared to the one day a week in about 1800.

Army chaplain and author on foxhunting and polo, Thomas Francis Dale gave an indication of the popularity of Market Harborough in the hunting scene in his 1903 book ‘Fox Hunting in the Shires’ available to download here. The hardest riding men, Dale reported ‘were flocking to the country’. Dale describes the convenience of Market Harborough for such sporting men. Pleasant accommodation was easy and reasonable to rent, or else there were numerous hotels with a long tradition of hunting customers. He also describes the first-rate railway service, allowing one to reach Market Harborough in two hours from St Pancras (fast by 1903 standards!). But he also highlighted the need for ‘big bold blood horses’ since the ‘fences are serious obstacles’, and in fact ‘two horses a day are a necessity’. He noted that ‘probably from four to six horses and a hack is the average number in most stables’ in Market Harborough at the time.

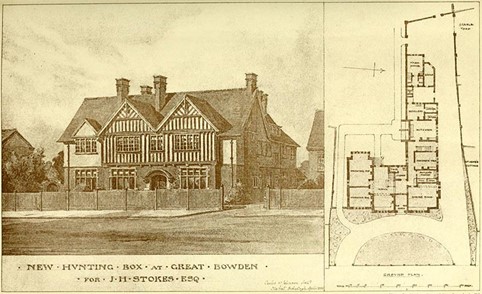

Fortunately, such horses were readily available in the area. Contributing significantly to the popularity and standing of Fernie’s Hunt and to Market Harborough in the equestrian world was the presence of probably the most successful breeder of hunters in England. This was John Henry Stokes who moved to Great Bowden, the village northeast of the town, and now a suburb. By 1900, he was living in Nether House on the village green, had added stabling and built up a successful horse dealership, selling horses to the nobility of Europe. These included the future King Edward VII, Emperor of Austria and Kings of Spain and Italy as well as most of the hunting aristocracy of England and continental Europe. He also supplied large numbers of lesser quality horses to the army for the Boer War and later the First World War, and two of his horses also became Grand National winners. To cater for his rich clients coming to Market Harborough for the hunt, Stokes acquired various large houses within Great Bowden and turned them into ‘hunting boxes’, or else demolished old cottages and put new ‘hunting boxes’ in their place. Hunting boxes were small houses or lodges with stabling rented out to those attending the hunt. Stokes also organised and financed the building of the Village Hall, completed in 1903, to provide a place of recreation for his grooms away from the six public houses in the village. Run on the lines of an Institute, it had both a Reading and Games Room.

Today, Great Bowden is now the home of the Fernie Hunt – the hounds have been kennelled here since the 1920s although foxhunting has been banned in England since 2004. Nevertheless, the Fernie Hunt carries out instead pre-set artificial scent trails while hundreds of people still gather in Great Bowden for the traditional Boxing Day meet each year.

Advertisements abound in local newspapers of the time indicating the need for both stables and grooms. George would have had no trouble finding work. For example, in 1901, Master of the Hounds, Charles William Bruce Fernie employed a stud groom plus four other grooms at his palatial 18th century home, Keythorpe Hall in the village of Tugby, 12 miles (about 20 km) from Market Harborough on the Uppingham Road. He also had 13 other servants according to the census return that year, to tend to his needs and that of his new wife Edith, 20 years his junior who he had married the previous year. Today, Keythorpe Hall is a luxuriously restored private house and walled garden, available to hire for bespoke events.

A good source of income for stud grooms were the fees involved when ‘standing’ horses were offered for mares to ‘try’. Advertisements to this effect were common in newspapers. Payment for the stallion’s service included a portion to cover the cost of groom. This seemed to be generally 2s 6d per stallion (about £10 or $20 AUD in today’s money).

The annual Fernie Hunt Horse Show further emphasised Market Harborough as being the hunting centre of England. It was first held in 1896 at Elms Park on Leicester Road (the area between Burnmill Road and Park Drive, now built on). The following year and thereafter it continued to take place on the cricket field in Fairfield Road, although it was temporarily halted during both world wars. After WW2, it continued in Dingley. A short, black and white Empire Newsreel (Reuters) showing Fernie’s Hunt Show in 1928 can be seen here. The slate at the beginning reads: ‘Beautiful animals meet and compete at Market Harborough’. If you look carefully, you will see the familiar church spire of St Dionysius in the background.

In the RAF

George enlisted a month after the creation of the RAF, formed on 1 April 1918, following the amalgamation of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and the Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS). He had already demonstrated his plucky nature by his shift to the Midlands while handling strong-willed horses was not for the faint-hearted. Now heading towards his mid-30s, he decided to try yet another new venture.

His service records show that George spent four months in the RAF, based in Castle Bromwich, nearly 50 miles (about 80 km) away, which today is on the outskirts of Birmingham. Castle Bromwich Aerodrome had been a privately owned airfield in the early years of the 20th century, built on former playing fields, which previously had been the site of 12th century Berwood Manor House. At the start of the First World War (WW1), the War Office requisitioned the land for the Royal Flying Corps and flying schools, building roads and other necessary infrastructure. It was used to train pilots and later to test planes. Around ten Royal Flying Corps and Royal Air Force squadrons resided at the airfield during and just after WW1. An old farmhouse dating from the late 17th century was used as the officer’s mess.

Our worlds collided again. I visited the site of the Castle Bromwich airfield in 2016. Then the home of Jaguar Cars since 1980, the factory had been originally constructed in 1939 to manufacture aircraft in response to WW2. It was here between 1940 and 1945 that 11,780 Spitfires and 305 Lancasters were built making an enormous contribution to the war effort. It’s still to be determined what George actually did in the RAF. One may assume that he did not fly, as his records say he was a Private 2nd class. This and Private 1st class denoted pay for non-technical staff when the RAF was formed in 1918. What we do know is that he was discharged medically unfit on 1 January 1919, after spending time in Parkhurst Military Hospital at Newport on the Isle of Wight. Parkhurst was a military hospital during WW1. Dating back to 1778 when it was a military hospital and children’s asylum, it became a prison in 1840, a training institution for boys sentenced and waiting for transportation to Australia or New Zealand. It is believed that around 4000 boys passed through Parkhurst. After transportation stopped between 1863 and 1869, it was briefly a women’s prison before transferring back to a male prison in 1869. As well as a WW1 military hospital, Parkhurst was the headquarters for the military units on the island and the central hub for clerical staff who searched records for missing soldiers. Since 1966, Parkhurst has been a top security prison, and is most remembered for its infamous inmates who had committed some of the worst crimes of the 20th century such as East End gangsters, the Kray twins; Moors murderer, Ian Brady; and the Yorkshire Ripper, Peter Sutcliffe.

The Three Swans

It seems that George did not return to working with horses when he came back from the war. Perhaps his failing health contributed to him taking a less strenuous job on his return to Market Harborough. According to the 1921 Census he was the ‘Hotel Boots’ (cleaned shoes, ran errands, did odd jobs), at The Three Swans on the High Street. Originally the Swan Inn and dating back to the 16th century, this hotel’s heyday was the coaching era of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when it was owned and operated by a local landowner who was also a partner in the firm that ran the Manchester to London coach service. It was during this time that it was rebuilt to create today’s existing frontage and obtained its striking wrought iron inn sign. Today, a booklet about its history can be downloaded from the hotel’s website.

It’s possible that George had worked for this hotel as a groom prior to him joining the RAF. The Three Swans certainly had stabling but not, it appears, after 1920, for I discovered through local newspaper advertisements that in April that year the hotel proprietor GC Cribben (also named as George’s employer in the 1921 census return), sold all the horses and carriages because he was ‘installing motor cars’. By December 1920, WH Stevens had taken over ‘bus cabs from Three Swans to station’. Times were a-changing for local grooms in town.

Incidentally, during this time, George Charles Cribben was one of the relatively short-term innkeepers who took over the Three Swans, after the hotel had remained in the same family for a considerable period. His tenure appeared to be only a couple of years, before moving onto another hotel in Derbyshire and then back to Kent from where he hailed. Previously he had been a professional golfer and designer of golfing irons at the Hythe Golf Club from 1902–1917.

Symington’s

George may well have continued to have worked at the hotel throughout the 1920s. When his only daughter Ada sadly died aged only 21 in 1929, one of the many wreaths at her funeral read: “With deepest sympathy, from the staff, ‘Three Swans’”, the kind of touching gesture one may assume would be undertaken for a long-time employee.

Ada’s death and funeral as reported in the local newspaper holds a light to numerous intimate details regarding their family. We learn she died “after a short illness patiently borne”, that her nick name was “Babs”, and that interestingly she called her mother “mam“, a term more commonly associated with the northeast of England or Wales. She had a fiancé, Fred “broken-hearted” and he, plus her parents were the chief mourners along with her uncle and two aunts, that is, her mother’s siblings who all lived locally. Almost 45 wreaths were sent to the funeral from family, friends, neighbours and work colleagues and each message of condolence is listed. They include members of the Brunning family “Ever-loving remembrance of dear Ada, from Grannie and all, Ipswich”. ‘Grannie’ would be Sarah, widow of Samuel Brunning who had died in 1916. At the time of the 1921 census, she was living in Whitton, a village centred on what was the main Ipswich to Norwich Road, and now part of Ipswich. “And all” one may assume referred to her youngest daughter Annie (George’s sister) and her family who also lived with her. Annie had married Richard Harding, a policeman from Kent and, at the time of Ada’s death, they had two small boys, Allan and George.

The most revealing are the condolence messages from work colleagues. They instantly give a clue to Ada’s place of work: “With heartfelt sympathy of dear Ada, from her fellow workers, Old French-room Suspender Department”; “With deepest sympathy from her fellow workers and staff, Highfield-street factory”; “With deepest sympathy from members of the building Department, Messrs R & W H S & Co, Ltd”. It seems clear that she is employed by Symington’s, that is R & W H Symington & Co Ltd, of Liberty bodice fame, and which began making corsets for fashionable Victorian ladies in the 1850s. By the 1890s they were one of the leaders in their field, exporting corsets to Australia, Africa, Canada and the United States. In Britain, the cotton industry was based in the Midlands, particularly Nottingham, so the company was perfectly placed in Market Harborough. However, they never marketed under their own name but produced many trade names of their own and for other companies such as Marks and Spencer.

Specialising in the manufacture of corsets using factory-based, mass production techniques, Symington’s was one of the first to use the US Singer sewing machine in Britain. The company became Market Harborough’s largest employer. Generations of families worked there. In the 1920s, social activities were organised onsite, including dances, concerts, and football games. Originally located in a disused carpet factory in Adam and Eve Street, their success resulted in the construction of a new factory in 1889 across the road that dominated the town, as it still does today but as the council offices, library and museum. Branch factories were built outside Market Harborough and the company also expanded worldwide, with factories in Ireland, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia.

Based on a reference amongst the condolence messages, Ada may have worked at their smaller Highfield Street factory, which Symington’s had taken over from a shoe manufacturing company prior to WW1. It was less than a 5-minute walk away from her home. Today, the factory is no longer there but was perhaps at the end of the street where there is now a new block of four houses following on from number 56.

By 1939, we discover that both George and his wife Emily were now working at Symington’s. According to that year’s England and Wales Register, George was a Corset Steel Straightener and Emily, a Corset Forewoman. They were still living at 41 Nelson Street, and we can see the number of neighbours who were also Symington’s employees, including several corset machinists as well as a corset hand worker, corset warehouse foreman, corset marker and corset overlooker.

Sadly, George lost his wife less than a year later. Emily died on 12 February 1940 aged only 50. Like their daughter, her funeral is reported in detail in the Market Harborough Advertiser and Midland Mail, and again we can glean numerous details about her life from the write up. She was known as Millie or Mill. Both her sisters Ellen (Nell in Fleckney) and Annie (Cis in Naseby) attended the funeral as did nieces and nephews. There were over 40 floral tributes that were accompanied by poignant messages of condolence from friends, relatives, work colleagues and Nelson Street neighbours. There was even a message “To Mrs Brunning with sympathy from friends, Admiral Nelson”, from the local pub, just four doors away from their home (and still there at 49 Nelson Street LE16 9AX). There was also a message from her Brunning relatives “with fondest love from Sister Annie and all, Belvedere-road, Ipswich”. This is in fact her sister-in-law, George’s youngest sister, Annie Harding, who with her husband Richard, now promoted to police sergeant, and younger son George, an auctioneer’s junior clerk, were living in a three bedroomed terrace house at 69 Belvedere Rd Ipswich (IP4 4AD).

The Symington’s employees are indicated by reference to various work sections: “G Dept”; “the Swimsuit Dept, Highfield Street”; “the Brassiere Room”; “the mechanics, electricians and building depts, R. and W. H. S”; and “Mrs. Pounds and the Highfield-street girls (White Room)”. As a forewoman, Emily or Mill as we now must call her, would have been known to many in her workplace and was obviously highly respected.

George died not long after his wife in early 1942 aged 57 but it seems with little fanfare. I have yet to find a tribute in the local newspapers that match those of ‘Millie’ or ‘Babs’. That seemed to be the end of the Brunning connection in Market Harborough although some of George’s wife’s family lived locally at this time, Millie’s brother John mentioned previously later moved to Nelson Street (at no. 22) while her niece Maud Osborne (her sister Annie’s daughter) lived at 3 Auriga Street, just around the corner from mum’s house today. Some descendants continued to live in Market Harborough till quite recently.

George’s sisters

George’s three sisters – Ellen, Louisa and Annie – went into domestic service in their teens or early twenties in the London area. Ellen emigrated to Canada some time prior to WW1 where she had two very short-lived marriages late in life. She died in 1921 aged 46 and is buried at Toronto’s Mount Pleasant cemetery. Both Louisa and Annie married police officers, Louisa to Ernest Brigden in London; and Annie, as mentioned previously, to Richard Harding in Ipswich. Louisa’s husband, Ernest was based at Aybrook Police Station in Marylebone. In 1936, Louisa and her 13-year-old daughter Joan moved to Ipswich a couple of years after Ernest’s untimely death, to be closer to her sister Annie. Louisa lived in Cemetery Road, a short walk away from Annie in Belvedere Road. Annie and Richard’s two boys Allan and George were very close in age to Joan. Joan tells the story of when they were bombed out of their home during WW2 when in September 1941, a German parachute mine landed on Cemetery Road destroying 75 houses. They went to live with her aunt Annie’s family for a few days before being allocated a council house while their former home was being repaired. Policemen continued to run in the family it seems, as after the war Allan Harding married Joyce Bristo, the daughter of an Ipswich police sergeant.

I have since discovered that another Brunning was married in Market Harborough (actually Little Bowden) about the same time as George. This was Edward Arthur Brunning who in 1909 married Ellen or Nellie Goode, a corset machinist of Little Bowden. Edward’s grandfather John Brunning was a shepherd, born in Icklingham so I feel there must be a connection. They were perhaps second cousins and may even have influenced George’s move to the Midlands. But that is more research for another day.

There are so many interesting threads running through George Brunning’s story that weave the past into the present. The Three Swans was a popular place for coffee with mum and her friends in her more active sociable days – it’s amazing to think that once, a not-too-distant cousin perhaps hurried through the cobbled courtyard to return a freshly polished pair of riding boots to a guest or run an errand. Symington’s former Adam and Eve factory site is where mum was not only a frequent visitor to the library but also volunteered there choosing and delivering books to the elderly; and finally, there is even a connection with Symington’s and mum’s home in Nithsdale Crescent. Symington’s once owned the land on which her house is built. The road gets its name in honour of the area where William and James Symington grew up. They were the original brothers who each started their own individual Symington’s empires in Market Harborough – centering around soup and corsets. They were born in the small Scottish market town of Sanquhar, in the picturesque Nithsdale valley within the border county of Dumfriesshire. Close to mum’s house, on the corner of Auriga Street and Northampton Road, you will find Nithsdale House, (65 Northampton Road, LE16 9HD), with its walled front garden, and name chiselled into the concrete pillars either side of the impressive wrought iron gates. Dating to about 1890, it was built by William Symington and remained in the family for some years. Apparently, it has a beautiful arts and crafts carved wooden mantlepiece in the sitting room.

William Symington was the brother behind Symington’s Soups, originally founding a company selling tea, coffee and groceries, then roasting coffee. He eventually invented dried pea flour that could be used to make instant soups just by adding boiling water. It was a great hit with soldiers in the Crimean war as well as Captain Scott’s first Antarctic Expedition of 1901-4. This Symington’s factory was on Springfield Road, eventually being acquired by Lyons and ending its days as the home of HP Sauce. That is where I started this blog post and where I’ll end, before I disappear down any more rabbit holes!

it was never the home of HP Sauce. That was Aston in Birmingham. Before production Wass transferred to Holland.

Thanks David. I know Birmingham was the real home of HP sauce before it went to Holland but there was a branch at MH wasn’t there? I certainly remember that sweet chutney smell pervading the town when I lived or visited there in c1989-1992.