So, we take up the story of my great aunt Lilian (Bruce née Cockrill) in the mid-1930s (and a quick reminder that you can find her in the family tree here).

Life after Llewellyn

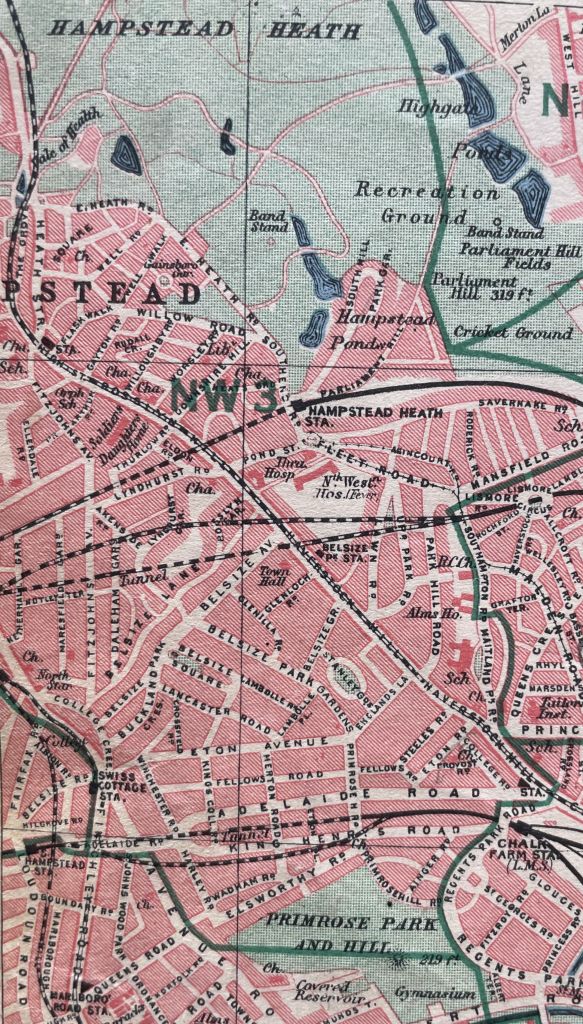

For whatever reason, Lilian’s marriage to Llewellyn Bruce did not last and she returned to her old life, lodging in large houses divided into flats and bedsits in Adelaide Road and then later in nearby Fellows Road, Swiss Cottage (London Borough of Camden).

Prior to her marriage, Lilian lived at number 97 Adelaide Road. From around 1936, she moved a few doors down to number 115 where we know she was living at the start of the Second World War (WW2). At the back of these houses, Lilian would have seen and heard the trains running north from Euston alongside Adelaide Road as they still do today. It was a dangerous place to be living during WW2 as the main railway line was a key target for the Luftwaffe (German air force). She no doubt encountered huge silver barrage balloons (obstacles to enemy aircraft) floating in the vicinity as well as anti-aircraft guns on nearby Primrose Hill. The latter was just a short 5-minute walk downhill from her house where she could experience the iconic view of the London skyline set behind the green parkland. She was also close running distance to Swiss Cottage and Chalk Farm tube stations, where many locals fled to the underground platforms during the London Blitz of 1940-41, when a German bombing campaign took place over Britain for just over 8 months resulting in two million houses being damaged or destroyed (60 percent of these in London).

Lilian was 38 at the start of the war according to the 1939 England and Wales Register, an invaluable resource for family, social and local historians. Taken on 29 September, the information was used to produce identity cards and, once rationing was introduced in January 1940, to issue ration books. For 115 Adelaide Road, Lilian is listed as a Secretary, Ladies Dept Clothing. One might assume this was in a department store in the West End. Others in the house share similar occupations, for example, Manageress Hosiery and Underwear, Shop keeper Dairy, HMOW (His Majesty’s Ordinance Works) Storekeeper. Lilian also states she is married but we know that she and Llewellyn never lived together again. Interestingly, Llewellyn declares he is single when he fills out the form for the same Register (see the previous blog for more details on Llewellyn’s ‘post Lilian’ story).

By the end of the war, Lilian had moved to another house, one street back and parallel to Adelaide Road, at 97 Fellows Road. Both Fellows and Adelaide Roads were built on land originally owned by Henry VI and later Eton College. Henry VI had founded this famous elite public school near Windsor in the 15th century. The names of the roads on the Eton College estate reflect their past, hence Fellows (referring to the College ‘Fellows’) and Adelaide, named after the reigning queen at the time that the road was significantly developed in about 1832.

Lilian was likely to have moved from Adelaide Road to Fellows Road due to much of the former street being heavily bombed out. We know that within a week of the Blitz starting in London in September 1940, that during a relatively light night raid, a bomb hit Adelaide Road and killed 12 people.

Number 97 Fellows Road was the address from which she wrote to my father in 1945 (as mentioned in Part 1 of this blog post). She stayed here until about 1949 when she moved again, this time a few doors down to number 107 where she stayed for the next 15 years.

Just like her Adelaide Road homes, both houses had multiple occupants, singles in the main while their names sometimes give a hint to their heritage. Further research has uncovered some fascinating details of their personal journeys. Lilian clearly lived in a cosmopolitan area, amongst artists, actors, shop assistants, waiters and waitresses, hoteliers and club owners, many of whom had a European background. I know from my own work-related research around the Holocaust that this was an area where many Jewish refugees and others fleeing persecution in Europe found sanctuary.

Meet the Neighbours

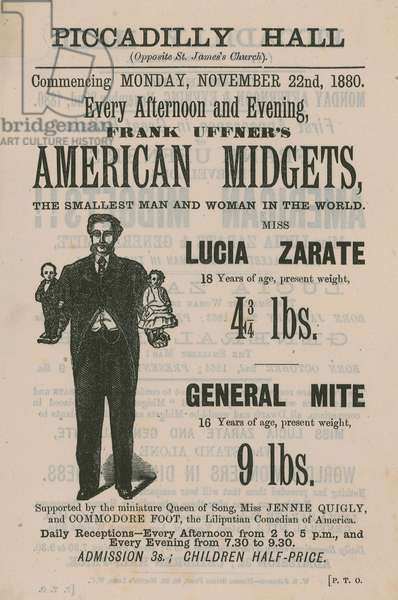

One can only speculate how much Lilian interacted with her close neighbours. For example, how chummy was she with aging Film and Stage Actor, George Langley-Bill who lived alongside her at 115 Adelaide Road during the late 1930s? Did he entertain her with stories from his days at the Garrick or Lyceum Theatres before WW1 or the time he chased a pickpocket through the streets of the West End as reported in the Reynold’s Newspaper of 1913? Then there was her neighbour, dark haired, dark eyed Basilio Cranchi, variously confectioner, caterer, refreshment house keeper. Did he describe to her his childhood in the beautiful Italian village of Ballagio on Lake Como? Or his adventures as a hotel waiter in New York, crossing the Atlantic in 1916 on the very same ocean liner that had taken the US Olympic team to Stockholm four years previously?

Similarly, how engaged was Lilian in her neighbours’ lives when she was residing at 97 Fellows Road? The year 1948 was a tumultuous time for some of them. It was the year William and Kate Itter’s daughter Irene, a teenage GI bride, returned from a failed marriage in America to live with them. Only two years previously, Irene had sailed with her baby daughter on the famous British ocean liner Queen Mary to re-join her husband in Missouri. Was Lilian privy to all their family’s woes?

Meanwhile young married couple, Thomas and Kathleen Binovec were also experiencing difficulties. In January 1949, 32-year-old Thomas reportedly fell under a Bakerloo line train at Swiss Cottage station although the Daily Mirror gave a somewhat more detailed and sensational version when it not only reported the outcome of the inquest – ‘suicide while of unsound mind’ but also the railway foreman’s failed struggle to save him. Thomas was a hotel waiter whose Czech father, also Thomas, had arrived from Prague before the First World War (WW1) and had served in the British army. Thomas Senior was manager of the Czecho-Slovak Colony Club near Regent’s Park. Later, his wife Blanche, the club’s bookkeeper, seems to have lived at 107 Fellows Road with Lilian while he was working as a hotel waiter in Canada. Remember Thomas senior as we’ll come back to him later.

Image © Reach PLC. Image created courtesy of THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD.

Likewise, we ask how well did Lilian know her neighbours at this latter house where she was to live until the mid-sixties? Some names stand out as being long term residents and with connected pasts. Stuart Wynn Jones lived at this address for at least a decade from 1955. According to an article by multimedia artist Ian Helliwell in The Wire (November 2012 Issue 345 p32), Wynn Jones was an ‘advertising man by day, avant garde film maker by night’ and ‘this radical hobbyist was part of a UK post-war boom in amateur sound and vision experiments.’ He was a member of the British amateur animation collective, the Grasshopper Group who made hand-painted abstract films with musical soundtracks. He is particularly known for Short Spell (1963) which was a winner in the Annual Ten Best competition organised by Amateur Cine World, receiving numerous screenings and appeared on TV on the BBC Tonight program in January 1958. You can view it here

He features in an article in Amateur Tape Recording Vol 2 No 7 Feb 1961 here where he is pictured at work in ‘his small studio-cum-bachelor flat in Hampstead, London’. Did Lilian hear some of his experimental sound recordings involving taps running, pieces of paper being torn, sticky tape being pulled off the roll, or piano chords?

All Things Bohemian

The North London area where Lilian resided was an enclave of European refugees at the time, and apart from the Binovecs, there were other Czech neighbours in the houses in which Lilian lived. For example, there were the Hnideks from Bohemia consisting of Joseph, a fur worker with his wife Antonie and daughter Olga. Olga married another Czech, Ladislav Corny Češek, who was a member of the Czechoslovak-manned fighter squadron of the Royal Air Force in WW2.

But along with Lilian, one name stood out as a consistently long-term occupant of 107 Fellows Road. Karel Jirasek. In fact, on the Electoral Register of 1949 they were the only occupants (at least the only ones eligible to vote). I began to dig deeper. Bear with me, as it will soon become clear where we are going with this!

When Lilian met Karel

According to the 1939 England and Wales Register, Karel aka Charles Jirasek was the Assistant Manager of a Travel Bureau at 37 Ainger Road in Hampstead (London NW3 3AT), not far from the Primrose Hill parkland. He was born on 19 November 1891 and advertised his intended naturalisation in the News Chronicle on 30 March 1939. Remember fellow Czech, Thomas Binovec Senior? He had also chosen to become a naturalised British citizen, advertising his intention on 21 October 1938. This no doubt was related to the then perilous state of their shared country of birth. A few weeks previously, the Munich agreement (the one where Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain brandished a piece of paper on arriving at Heston aerodrome proclaiming ironically ‘Peace for our Time’) had led to the Sudetenland (where ethnic Germans lived in Czech regions) being annexed to Germany. Soon Czechoslovakia ceased to exist, and by mid-March 1939, Nazi Germany had taken over all of Czechoslovakia, proclaiming both the Slovak state and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Karel, it seems, was intent on staying in Britain and to not return to his homeland.

Image © Successor rightsholder unknown. Image created courtesy of THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD.

Like many Czechs living in Britain at this time, Karel arrived at the time of WW1. There were around 1,000 Czechs and Slovaks living in London back then, the majority working as waiters just like Thomas Binovec who had arrived from Prague in around 1910. Like many others of their kinsmen, they wanted to show their allegiance to the allies by joining the British army, but as citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire they were considered ‘Aliens’ and prevented from doing so. However, rules were eventually slackened as the war necessitated increasingly more manpower. Both enlisted around the same age: Thomas was 24 and Karel 25.

According to his military records, Karel was a 5’ 8” tall seaman, born in Nymburk, a town in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic, almost 60 km (just over 35 miles) northeast of Prague. He was assigned to the Royal East Kent Regiment or ‘the Buffs’ in June 1917 and was immediately sent to Canterbury for training. By March the following year, Karel was posted overseas where he suffered gunshot wounds to the neck, forearm and left knee and presumably sent back to ‘Blighty’. In 1919, he was transferred to the 11th Hampshire Regiment and discharged from military service on 14 November 1920. According to his enlistment papers, he was living (assume lodging) at 48 Fitzroy Square (W1T 5BS), a beautiful Georgian square known as Fitzrovia near London’s Euston Road and Regent’s Park. Built in the late 18th century by noted architect Robert Adam and his two brothers, the square was originally designed to provide London residences for aristocratic families. These days it’s used for film locations (think ‘The Crown’, ‘Vanity Fair’ etc) and a prime location for offices and celebrity homes. In fact, English film director, producer and screenwriter, Guy Ritchie, is based here, buying two adjoining mansions after his divorce settlement with ‘Queen of Pop’ Madonna. However, on further investigation, Karel probably lodged at 48 Fitzroy Street, which carried on from Fitzroy Square, just around the corner. Occupants in the 1911 Census indicate that many European emigrants – French, German and Swiss – were living here. Today, it is listed as a Georgian grade II period townhouse built in 1790, and stepping outside you would see the BT Tower literally towering above you.

Still described as a seaman, Karel appears to have returned to London from Hamburg in 1923 on a German cargo steamer, the SS Elbe.

It is likely that Karel and fellow Czech expat, Thomas Binovec Senior knew each other. By the start of WW2, Thomas was the manager of the Czech-Slovak Colony Club near Regent’s Park, where it is probable that Karel frequented. At the time of Czechoslovakia being annexed by Nazi Germany, Binovec was reported in a newspaper article (Yorkshire Post, Thurs 16 March 1939, p8) as saying that ‘300 members of their club had served in the British army’. In the same article, an interesting aside is that the first President of the Czechoslovak Republic, Tomáš Masaryk had penned the constitution in the club’s writing room during his stay in London in the early years of WW1.

So, we can suppose that perhaps Karel met Lilian through the Binovecs: we know that she had lived in the same house in Fellows Road in 1948 as Thomas Binovec’s son and daughter in law, as well as later with his wife, Blanche in 1956 (along with Karel).

Looking at the Electoral registers we can see that Karel and Lilian were living at 107 Fellows Road, Hampstead (London, NW3 3JS) from 1949 to 1965. Accommodation was difficult to come by in the years immediately after the war with so many homes destroyed and rebuilding taking place. It was around 1948/9 that number 107 became available. Since about 1900 it had been the family home, known as ‘Dalkeith’, of Edward Dalziel and his nine children. From the mid-19th century, Edward ran a well-known wood engraving firm with his brother George. They worked on early numbers of Punch and Illustrated London News and collaborated with the Pre-Raphaelites on various illustrated publications. The last member of Edward’s family, his unmarried daughter Dora, died at number 107 in 1947 and later in the year all her valuable antique furniture and effects were sold at auction. It is then, one assumes that the house was renovated and turned into flats and available to rent, and when Lilian moved there from number 97, and Karel from Ainger Road.

Leaving London

In 1965, the bombed out parts of Adelaide Road began to be developed and replaced by the Chalcots Estate, a council housing estate. For example, a 20-storey block of 72 flats called Blashford, (NW3 3RX), one of five tower blocks that made up Chalcots, was built on the site of Lilian’s former home at number 115. The land where her home at number 97 stood became the Adelaide Nature Reserve and the site of corrugated iron sheds which today houses the vehicle repair shop, Modern Motor Ltd.

At this time, Lilian was in her early 60s and it seems that she decided to leave London and live out her final years, as was traditional for British retirees, out of the city and close to the sea. Her new home was a semi-detached, two bedroomed house in Seabrook, a small village close to Hythe on the south coast of Kent. It backed onto woodlands, and it was a 20 minute or so walk down to the beach, where one had a choice of turning left to Sandgate or right to Hythe and the start of the 45 km (28 mile) long Royal Military Canal, originally constructed as a defence against the possible invasion of England during the Napoleonic Wars. It was also a 10-minute drive to Folkestone where, like today you can get trains to London or take a ferry across the channel ‘to the continent’.

We know this because her address – 19 Woodlands Drive, Seabrook, Hythe, Kent (CT21 5TG) was given on her probate records when she died there on 9 February 1972. But what I next uncovered explains my previous preoccupation with all things Czech.

I decided to continue following the life of Karel aka Charles Jirasek and, bingo! According to his probate records, Charles died at the same Hythe address on 20 March 1967. Both he and Lilian had moved there in the mid-1960s and one can assume that they were living together as a couple for around 20 years, although there was no evidence of them ever being married. I also realised the possible motivation for moving to Kent. It might have been because Charles had been in ‘The Buffs’, the Royal East Kent Regiment during WW1 when he would have had memories of training around Canterbury, about 32 km (20 miles) away.

Then, at last, I found the final piece to the jigsaw, Lilian’s last resting place which clarified her relationship with Charles. At first, I couldn’t find her but through the BillionGraves website I found Charles, buried at the nearby Hawkinge Cemetery and Crematorium, (Aerodrome Road, Folkestone Kent CT18 7AG). The crematorium is built on the site of an old airfield used by Spitfire and Hurricane pilots during the Battle of Britain. Interestingly, the 1969 movie Battle of Britain was largely filmed at Hawkinge and the Jackdaw public house at Denton, about 8 km (5 miles) away.

Finding Lilian

And then when I found Charles, I found Lilian. His gravestone has a simple epitaph ‘In Loving Memory Of Charles’. These must be Lilian’s words; and when she died five years later, she was buried with him. At the bottom of the gravestone it reads … ‘and of Lilian Dorothy Bruce’. However, because of incorrect online information it was impossible to find her easily. BillionGraves gave her name as Lilian Dorothy Jirasek, and had also wrongly transcribed the headstone as Lilian Dorothy Price rather than Bruce.

England CT18 7QU. Courtesy of BillionGraves (SteveN photographer, ljayne123 transcriber, March 2018)

It was a somewhat breath-taking moment to find her. I felt I had got to know my great aunt Lilian during my online digging and had become quite fond of her. But the headstone is worn and looks uncared for. No-one has probably cared for over 50 years. Hopefully, this will change. I have already amended the online details on BillionGraves and one day, I hope I can visit Hawkinge and stop to remember Charles and Lilian, and the life we never knew they had together.

And what of the ‘madame in Soho’ anecdote which was part of family folklore and mentioned in Part 1 of this blog post? We may never know the truth behind this throwaway line – was this accurate, was it slander, or was her lifestyle just misunderstood? Her association with foreigners, sailors, artists, clubgoers may have raised eyebrows within some corners of her East End background while similarly her short lived marriage and living ‘in sin’ was perhaps frowned upon within the social mores of the time. One hopes that sharing this story online might one day bring forth some new information because although I have constructed something out of almost nothing, there are so many questions left unanswered! Just a photo would be fantastic!